Three Ways We Are Hurting Our Children

Leer en español

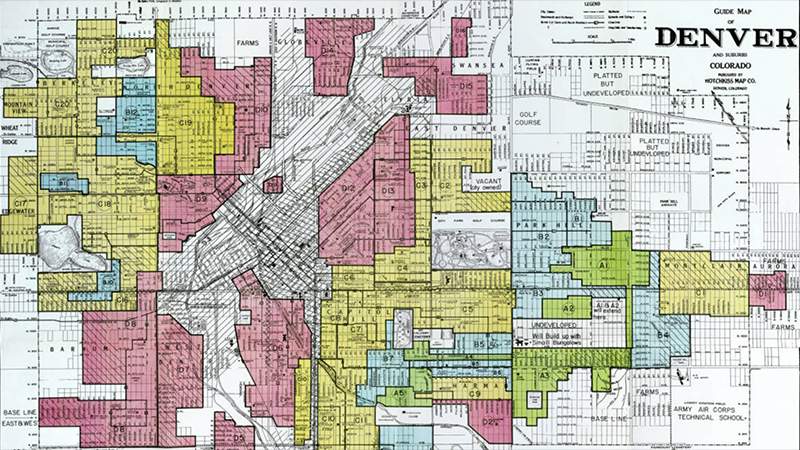

Underlying present-day inequities are policies like “redlining,” which denied low-cost mortgages to people living in neighborhoods with large concentrations of people of color. Image of a 1938 redlining map of Denver via Denver Public Library

By Kristin Jones

Every year, the Colorado Children’s Campaign publishes a compendium of facts and figures related to the health and prosperity of children in the state. The report, called KIDS COUNT, compiles data on things like the child poverty rate, high school graduation statistics and infant mortality.

This year, the nonprofit behind this report went further, tapping insights from communities around the state and history lessons to dive into the root causes of racial and economic barriers that hold Colorado children back.

Colorado Children’s Campaign, a Trust grantee, also sought guidance from a diverse cohort of nonprofits that are funded as part of our Health Equity Advocacy strategy.

The result is a report—well worth a read in its entirety—that is focused on deep inequities baked into our system.

Here are three of the man-made structures the 2017 KIDS COUNT report identified as holding back children in our state, with real consequences for their health. (All of this information comes from the report, which includes detailed sources and citations.)

1. Segregated Neighborhoods

It’s no accident that our neighborhoods are sharply divided by race and ethnicity.

Racially restrictive housing covenants—which became common in the U.S. starting in the 1920s—pushed people of color into isolated areas. Compounding this problem, federal programs launched in the 1930s with the intention of helping people afford low-cost mortgages deliberately excluded those areas with a large concentration of people of color.

In Denver, for instance, people living in the present-day neighborhoods of Five Points, Globeville, Elyria-Swansea, Sun Valley, Valverde and Barnum were denied access to mortgages that would have allowed them to build wealth through home ownership.

These policies contributed to a deep and persistent racial wealth gap that even income increases can’t bridge. As of 2013, the average white household in America had 10 times the wealth of a Latino household, and 13 times that of a black household.

Today, discriminatory lending policies persist. Native Americans living on reservations, for example, have limited access to conventional home loans. That’s because of federal policies by which reservation land is held “in trust” by the government, limiting banks’ ability to repossess or foreclose on land in the case of default. That makes banks reluctant to lend.

Meanwhile, as recently as 2006, black or Hispanic families making more than $200,000 a year were more likely to be given a subprime mortgage than white families making less than $30,000 a year. Subprime mortgages, which became famous for catalyzing the economic collapse of 2008, are more expensive for borrowers and offer less favorable terms.

What’s wrong with segregated neighborhoods? For one thing, neighborhoods with high concentrations of people of color tend also to be poorer neighborhoods, for some of the same reasons outlined above. Poor black and Asian children in Colorado are about three times more likely to live in areas of concentrated poverty than poor white children. Even black, Hispanic and American Indian children who aren’t poor are as likely to live in neighborhoods of concentrated poverty as poor white kids.

Concentrated poverty is another way of saying a lack of resources—resources that can be used to educate children, promote socioeconomic mobility, provide healthy food and opportunities for physical activity and recreation, or protect against environmental injustices like industrial dumping or lead poisoning. These are all factors that go into how long a person lives, and how well.

One of the bitter ironies of the kind of gentrification that we’re seeing in cities around Colorado today: Just as these kinds of investments begin to reach previously segregated neighborhoods like Five Points and north Denver, many of their original inhabitants are pushed out as rent becomes unaffordable.

2. Segregated Schools

In Colorado, 41 percent of Hispanic students and 45 percent of black students attend a school in which students of color make up at least 75 percent of the student body. Only 4 percent of white students attend a school like this.

Denver Public Schools is the most segregated system in a deeply segregated state. A perfectly integrated school system in Denver would mean that the average white student attends a school in which 77 percent of the students are children of color; very few do.

Segregated schools are a prime reason Colorado children aren’t reaching their potential. Again, their segregation is no accident.

A U.S. district court found in 1973 that Denver Public Schools was intentionally segregating its schools in violation of the constitution. A court order forced the school district to desegregate, mainly by busing students across neighborhood lines. The order was lifted in 1995, when a judge found that “the vestiges of past discrimination have been eliminated to the extent possible.”

Those vestiges proved hardy; since then, Denver Public Schools have resegregated. In 1996-97, for example, Manual High School was 41 percent black, 15 percent Hispanic and 44 percent white. By 2016-17, it was 40 percent black, 48 percent Hispanic and just 6 percent white.

Meanwhile, a 1974 U.S. Supreme Court decision limited the policy tools for integration across school districts. So, for instance, while Littleton’s school district has 27 percent students of color, and neighboring Sheridan has 87 percent students of color, they can’t be compelled to integrate.

Our schools are separate, and they are unequal. In highly segregated schools in 2013-14, nearly a third of teachers were in their first or second year of teaching, compared with just a sixth of teachers in less segregated schools. In Denver Public Schools, 90 percent of teachers in primarily white schools are rated as highly effective in the district’s performance evaluations, compared with 63 percent in schools where most students are children of color.

High-poverty schools struggle to retain teachers; they frequently offer fewer opportunities for advanced coursework; and they are tasked with teaching classrooms full of students who may be dealing with hunger, homelessness and the toxic stress of poverty—all without the resources available to wealthier schools.

Federal policies allocate school funding by local property values, and that makes these inequities worse. For instance, in the Aspen school district, serving mostly white students in Pitkin County, per-student property values are assessed at 76 times the rate of those in the Sanford school district in largely Hispanic Conejos County.

There’s arguably no single factor more important for the lifetime health of a person than education. Racial inequities in education are a key driver of racial inequities in health.

3. Policies That Punish Working Families

From the first moments of life, a child’s health is deeply dependent on the health of their parents—particularly their mothers. But for many families, the birth of a child introduces them to policies that add stress, or push them to choose between making a living and caring for their loved ones.

Fewer than half of Colorado parents are eligible for the three months of unpaid leave that parents of newborns receive under the federal Family Medical Leave Act; employees aren’t guaranteed the leave if they work for small businesses or have been employed for the same company for less than a year. Far fewer can take advantage of unpaid leave; going without the income is simply impractical. Nationwide, just one in four Hispanic parents and one in three Asian-American or black parents can take advantage of unpaid leave.

Mothers who are unable to take at least three months of leave are more likely to experience depression. And maternal depression puts children at higher risk for a range of cognitive, emotional and social difficulties.

The lack of affordable, high-quality child care is another factor that can push parents out of the workforce or into financial straits. It can also impact a child’s development. Only half of eligible Colorado children were enrolled in nursery school, preschool or kindergarten between 2011 and 2015.

Again, children of color were less likely to be enrolled than white children. In the Denver metro area, American Indian, black and Latino children are five times more likely than their white peers to live in high-poverty neighborhoods with no accredited early education center.

The health outcomes of deep inequities across our neighborhoods, schools and public policies are visible and tragic. Black mothers in Colorado are almost twice as likely to experience pregnancy-related depression as white mothers. Their babies are much more likely to die within their first year of life. Their children are less likely to graduate from high school, and more likely to live in poverty, with all the toxic stress that goes along with that.

These are all complicated, interrelated issues. But if there is one overarching takeaway from the 2017 KIDS COUNT report, it’s this:

“We learned that so many of these barriers are caused by public policy,” said Kelly Causey, PhD, who heads the Colorado Children’s Campaign, “and they can be undone by public policy.”