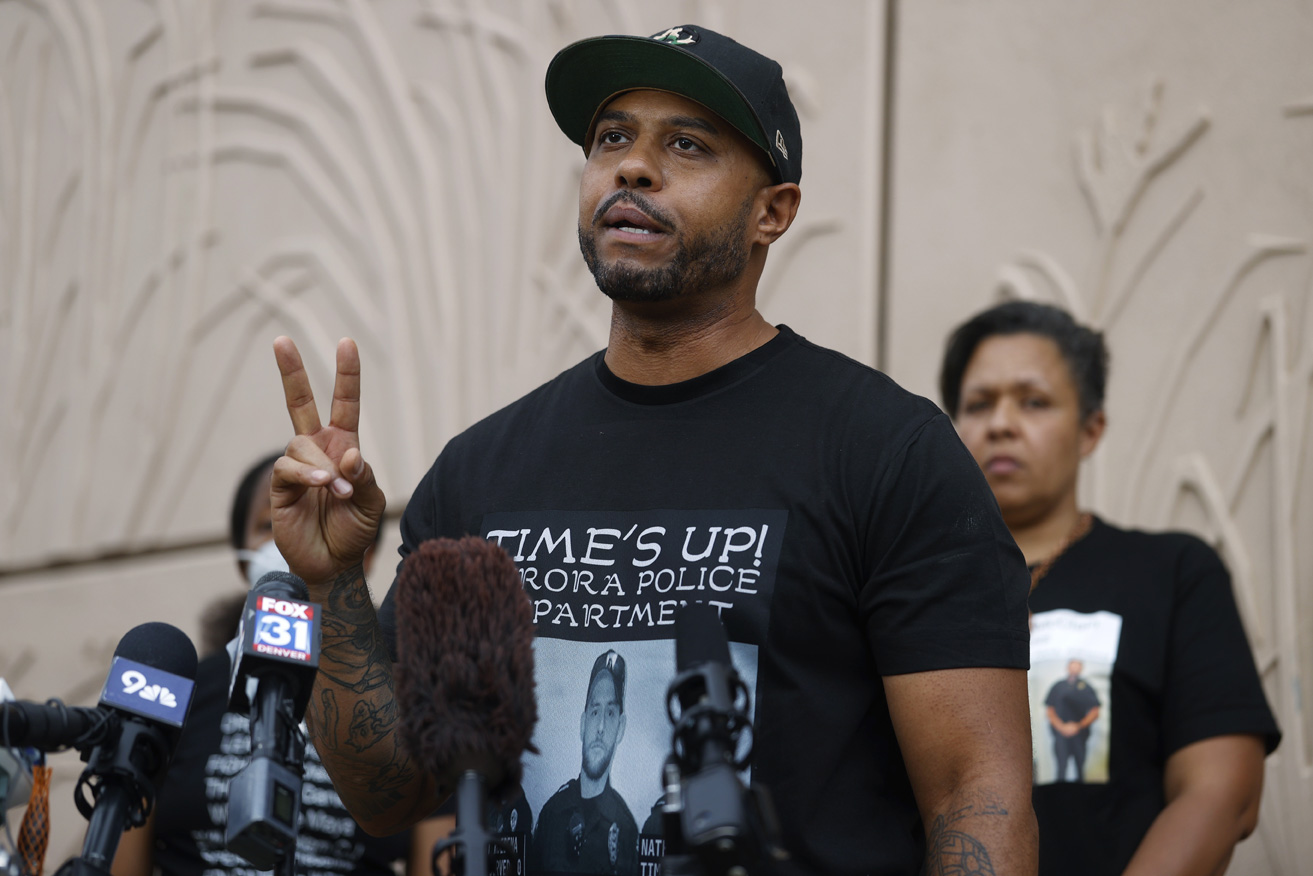

Terrance Roberts speaking at a rally in Aurora, Colo. in July 2020. Roberts is at the center of a new book by journalist Julian Rubinstein. Photo by David Zalubowski/AP/Shutterstock

Terrance Roberts speaking at a rally in Aurora, Colo. in July 2020. Roberts is at the center of a new book by journalist Julian Rubinstein. Photo by David Zalubowski/AP/Shutterstock

Julian Rubinstein is the author of a new book, The Holly: Five Bullets, One Gun, and the Struggle to Save an American Neighborhood, and my colleague at the University of Denver. Rubinstein was raised in Denver and has spent the last several years trying to better understand systemic and institutional racism in a city and a region that, at least externally, is seen as not having these deep issues that have so roiled our nation. Despite the city’s connection to the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s, a decades-long record of deliberate acts of discrimination by police and other government authorities, and a federal judicial finding that the Denver Public Schools were deeply segregated, Denverites have long neglected dealing directly with the consequences of this past.

Drawing on rich research and extensive reporting, Rubinstein details a history of neighborhood and demographic change, political activism and government, as well as philanthropic behavior, that greatly destabilized a neighborhood that had been at the center of Denver as well as the nation’s school desegregation battles in the 1960s and 1970s.

The story’s main protagonist is Terrance Roberts, who had risen to prominence locally and nationally as a peace activist after years in the Bloods gang. Roberts served a decade in prison on several felony convictions and emerged from that time as an anti-gang leader centered in the very section of Denver he used to operate in as a Blood. In 2013, Roberts shot gang member Hasan Jones moments before a peace rally that Roberts had organized was supposed to begin.

The resulting coverage, trial and aftermath of the shooting was centered around the Holly—formerly a shopping center and anchor of community gathering in northeast Denver that was undergoing a redevelopment after a fire burned it to the ground. The neighborhood’s incidence of violence over the years revealed the deeper roots and continued perpetuation of racism in the city.

Tom Romero: The book’s subtitle situates the events and the larger history in Park Hill in northeast Denver. What makes this story and this neighborhood particularly American?

Julian Rubinstein: The first thing that comes to mind is not probably one that a lot of people necessarily think about: It is the fact of gang violence and the gang war that is happening in almost all of our American cities, in both urban and suburban areas.

In America, it’s publicly accepted that the longest-running war in American history is in Afghanistan, but we have more than four decades of a war going on in our own streets, and it’s a war that isn’t really very well known or certainly not very well understood—and, unfortunately, I would say that that is sort of one of the most American things about this story.

I would also say that the gang violence in Denver is not an inner-city problem. The heart of the book takes place in the neighborhood of Northeast Park Hill, a prototypical exurban place. While the neighborhood experienced its white flight that started in the ‘60s and ‘70s, there’s in the last decade been a switch. A lot of white people have moved back into the cities and neighborhoods like Park Hill. We have these patterns of developments, redevelopment and gentrification. And so you have the often minority population, whether it’s Black or Latino, that is experiencing higher rates of poverty and lower incomes, and also over-policing of these neighborhoods. Together, these forces are pushing these communities to other suburbs like Aurora or Green Valley Ranch. And guess what? That is where gang violence is rising.

And yet the gangs are holding on to those areas that have meaning, including Holly Square, which ultimately had so much meaning to Denver’s first Blood gang. You have this center inside of a neighborhood that’s dramatically gentrifying, and the result is the Black population is significantly reduced over the last decade. But gang violence still remains there. Because they are so connected, they don’t want to give up that sort of homeland of sorts of theirs. This is all what comes to mind when I think of this as an American story.

TR: The decades-long gang wars that you describe made me think of Michelle Alexander’s book The New Jim Crow, which identifies and centers current state-sanctioned racial violence as being directly connected to the war on drugs, which is happening at the same time as the rise of gangs in the 1980s that you describe. Can you elaborate more on the connection between the war on drugs with the war on gangs, but also bring that story and connection to the present day?

JR: So when I was working on this book over the last seven years, I read The New Jim Crow and I would say that not only does it pertain especially to everything in Michelle Alexander’s book, I would say it pertains particularly to the neighborhoods I just discussed, because those are the places where government, law enforcement and all the powers that be are part of the criminal justice industrial complex.

In these neighborhoods, long before the Bloods and Crips rose in the 1980s, there were gangs in Denver. But unlike the modern gangs, the earlier gangs had a real connection to activism. For example, after the Watts riots in 1965 in Los Angeles, many gang members quit their gangs and banded together and became part of the local and national Black civil rights and Black Power movement.

The downfall of the political activism of former gang leaders was the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s Counter Intelligence Program under J. Edgar Hoover and the deliberate targeting of Black leaders. In operations run by law enforcement, these leaders were killed, others were prosecuted on false charges and sent to prison, others were defeated by harassment by law enforcement and bogus arrests and charges, like Lauren Watson, the Denver Black Panther leader. His life was ultimately destroyed in dealing with the emotional and community toll of police surveillance and violence.

In that vacuum rose a new era of modern street gangs, and in Los Angeles one of those young leaders was Raymond Washington, who founded the Crips. He wanted to start a new gang as something like the Black Panthers. But it also came at a time when guns and drugs had arrived and the suppliers, particularly of crack cocaine, had connections to the government in the form of the CIA.

At the same time that Reagan started his war on drugs, cocaine washed into Los Angeles, with the knowledge of the U.S. government. This took it to a new level, and suddenly you had an entire generation of people that could fill prisons convicted for offenses under the war.

A huge new government and private-policing industry emerged. The most recent example, which is at the center of my book, is Project Safe Neighborhoods. Its reputation, if not its reality, is as a premier “anti-gang” and “anti-gun” program that is deployed in these neighborhoods.

I can only say anecdotally, but it is likely no coincidence that this program is often deployed in neighborhoods that are undergoing gentrification. This is a continuation of what Michelle Alexander wrote about in The New Jim Crow, which is that the targets of America’s criminal justice efforts continue to be aimed at neighborhoods and communities like those living in Northeast Park Hill in Denver.

TR: Part of the American nature of the story is the struggle with race. You grew up in Denver, moved to New York, and then returned and came to know intimately all of the parts of this story. When it comes to the story of race in Denver and Colorado, what makes this narrative or understanding different?

JR: What’s particularly interesting to me about this neighborhood is that it was a place in 1947 that then Mayor Quigg Newton (who had succeeded Benjamin Stapleton, a Ku Klux Klan member) had called out Park Hill as a place for a purposeful integration. It was going to be this bold experiment to show how forward-looking Denver was. The promotion of the way that the neighborhood wanted to be, versus the reality, was very different.

This is a neighborhood that if you look through all of the materials about its development in the 1950s, there are all these constant affirmations and love letters about how this place was so progressive and liberal. But less than a decade later, Northeast Park Hill was one of the most dramatic examples of white flight on record, going from almost entirely white to almost entirely Black in 10 years. Soon thereafter, the neighborhood fell to all of the social ills that we have seen in other Black neighborhoods as a result of systemic and institutional racism.

TR: The book is structured as a series of acts, and I think you deliberately are making the argument that this story in Denver is akin to a Shakespearean tragedy. Tell us more about the hero. What are the events that contributed to his downfall? And what does redemption look like—from both an individual and larger societal perspective?

JR: One of the most interesting things to me about this story is all of the dramatic turns. As I started my research and writing the book, it almost felt like one of those rare stories where there is a tear in the social fabric and this African American former gang leader becomes accepted as a leader in the redevelopment of his neighborhood.

This is Terrance Roberts, the main character in the story, whose grandmother was one of the first Black residents in this neighborhood, when she moved in 1960. Roberts goes from being a middle school honor student to becoming a gang member within a year or two. This is in the early ‘90s, where the modern gangs, like the Bloods, have really risen and become a major part of this neighborhood.

Roberts joins a gang and becomes heavily involved. He eventually serves 10 years in prison and seems to have this real turnaround in his thinking. He’s clearly an incredibly intelligent and capable man who is from this neighborhood and he wants to be involved in the redevelopment of Holly Square, particularly in the wake of the destruction of this whole shopping center that the Crips burned down as a result of the gang violence. This seems like a story of redemption.

But much like the aspirations and reality of Park Hill, complications soon arise. It’s no surprise that Roberts is not the only one interested in redeveloping the Holly. There are a lot of other powerful interests in Denver that push him out as soon as Roberts starts to show that actually maybe he’s not totally on board with everything that is being proposed, and he’s the kind of guy who’s actually going to speak his mind. It didn’t take long and he was out.

This all provides the foundational context to explain what preceded the day in which Terrance Roberts then shoots a young gang member at his own peace rally in 2013. The book then details that for roughly a year and a half leading up to the shooting, there was a series of events in which Roberts had clearly fallen out with all of the powers that be around the Holly—from the City of Denver, The Denver Foundation and Anschutz Foundation, who were the primary investors in the redevelopment of this historic African American landmark, to the Boys & Girls Club, the Denver Police Department (which had undercover operations going on), and the gang that he was trying to eliminate. [Editor’s note: The Denver Foundation receives funding from The Colorado Trust.]

What is very complex but important to consider is the connections between all of these groups and their connection to Terrance Roberts’ downfall. In terms of redemption, particularly from a larger societal perspective, it would require those who are most invested in Holly Square, the foundations in particular, to actually act in the way they say they are going to act and support what they say they support.

I would say there is a powerful nonprofit industrial complex that maintains its power by continuing to serve each other, not necessarily the communities it says it is serving.

TR: And how would you change that?

JR: I think that there needs to be a way to truly bring all sorts of stakeholders to the table, because what happened, I think, in this story is that certain people actually don’t have any real say in decisions that are made. We need to find a way to actually give real voice to all of the players. The nonprofit industrial complex and related government and police agencies don’t have a lot of incentive to actually change.

Another specific thing, in terms of the Holly and in terms of the American story of gang violence in our communities, is to question the scope of law enforcement funding. Law enforcement has long controlled the lion’s share of the funding for people like Roberts who want to do good, community-based anti-gang work. When his problems really started to escalate was when he resorted to taking funding from Project Safe Neighborhoods, which Roberts found himself at odds with over how that money should be used. I would suggest that that law enforcement doesn’t necessarily have the same goals as an independent social service effort, and that needs to be addressed. Law enforcement is always trying to do these kind of neighborhood-type efforts, but unless you detach the policing from the social services, I don’t know that they’re going to gain the trust they would want in the community.

I have been pressing the City and County of Denver regarding the use of active gang members who are working under the city getting funding as anti-gang activists. It really raises a lot of questions. One of the most important things that anti-gang activists need to be is role models for vulnerable youth. If instead the people in those roles are still active gang members, representing a criminal lifestyle, the results are not going to be good and, in fact, they have been terrible. Since the city started pushing that approach in 2015, gang violence has gone up and up—whereas when Terrance Roberts ran an independent street effort in northeast Denver called the Colorado Camo Movement, the city’s gang violence fell to an all-time low.

It does make one have to wonder if what we are looking at is a part of the criminal justice industrial complex— something like an urban war industrial complex—that doesn’t actually have an interest in eliminating gang violence? Addressing issues like these are some things that can hopefully speak to all of the powerful interests that have been kind of having their way.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and length.