Alessandra Bullis’ clinic sits on the corner of Cripple Creek, a small town of around 1,200 people about an hour drive west of Colorado Springs. A nurse practitioner, Bullis has been serving patients here for almost three years. “It’s primarily a casino town with an older population,” Bullis said.

In nursing school, Bullis wasn’t taught about gender-affirming care, and she noticed that kids in Cripple Creek who don’t fit into the gender binary didn’t have any health care providers to turn to. “This population of rural kids in this setting don’t get a lot of attention paid to their sexuality and their gender,” she said.

A growing number of people are identifying as transgender or rejecting the gender binary. According to the Williams Institute at the UCLA School of Law, an estimated 1.4 million adults in the U.S., or 0.6% of the population, identify as transgender—almost double an estimate from roughly a decade earlier. And according to a 2017 GLAAD poll, 12% of millennials identify as transgender or gender nonconforming.

Yet study after study show that health care professionals like Bullis aren’t receiving adequate training in transgender care.

In Colorado, there is an organization working to solve this problem. Called the Extension for Community Health Outcomes, or ECHO, this nonprofit offers virtual, interactive classes on complex health issues to providers outside of major metropolitan areas.

Starting in 2020, ECHO Colorado launched a monthly class dedicated to teaching people about gender-affirming care, which attracted 45 providers, including Bullis, from Colorado and surrounding states. Classes covered topics including proper terminology, creating an inclusive environment and managing a patient’s hormones. The hope moving forward is that a growing number of providers across rural America will learn these lessons, thus expanding access to gender-affirming health care.

The ECHO approach was created in 2003 by liver disease specialist Sanjeev Arora, MD, at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque. His goal was to mentor rural providers on how to treat hepatitis C patients who lacked adequate care and couldn’t make the trip to a city. Almost two decades later, the program has spread to many other states and offers classes on health conditions including opioid addiction, diabetes and HIV.

Using the foundation set by Arora, ECHO Colorado offered trainings on gender-affirming care. The monthly classes were so popular that they expanded the program this year to include a four-week bootcamp that focused on proper terminologies, hormone therapy management, surgical options and supporting patients’ mental health.

Along with attending lectures, providers shared their own clinical cases and received consultation from specialists on how best to handle certain situations. “They want you to be engaged,” says Sara Gallo, PA, who attended the bootcamp and works at Care on Location, a Denver-based startup working to improve access to telemedicine care for Medicaid, rural and other underserved populations. “It was such a safe space to talk and ask questions without feeling like you might be judged.”

The course, which wrapped up at the end of February, had 90 providers from states including Colorado, Kansas and Wyoming.

“Data suggests that primary care providers aren’t comfortable even with routine trans care,” says Micol Rothman, MD, an endocrinologist at the UCHealth Integrated Transgender Program who helps teach the ECHO Colorado classes. For example, trans men who still have a cervix require a Pap smear to test for cancer, something that some providers aren’t comfortable doing: “So many patients have experiences of having to teach their providers these things. It’s exhausting.”

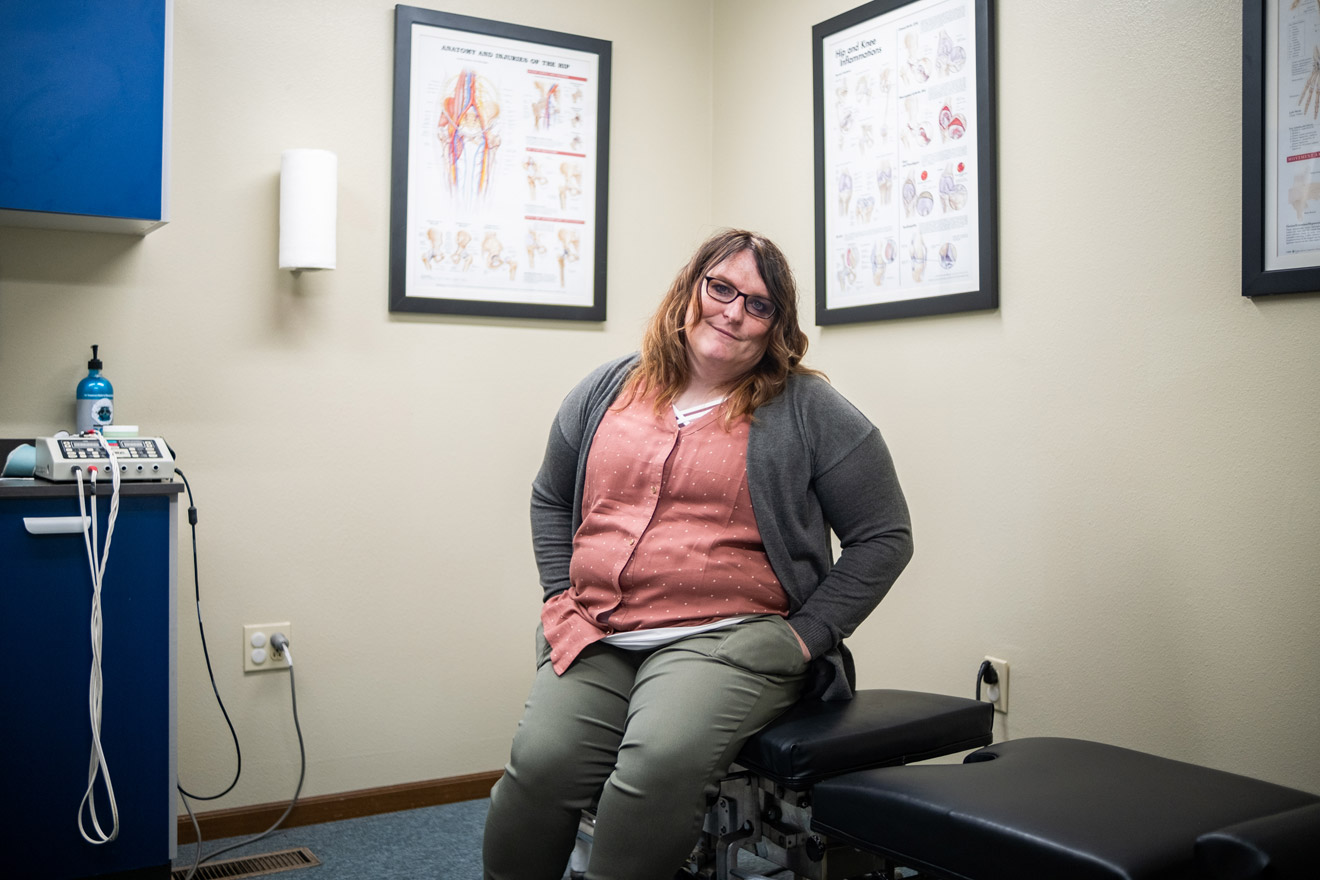

Tori Gleason has seen this knowledge gap firsthand—both as a provider and a patient. Gleason is a sports chiropractor in the small town of Goodland, Kan., located about 19 miles east of the Colorado border. At six years old, she knew she was different and describes her experience as akin to knowing she was left-handed but being consistently told to use her right hand. “You’re looking for everything and anything that makes you congruent with the world,” Gleason says.

Gleason discovered she was transgender in middle school but didn’t come out publicly until she was 36 years old, costing her house and her marriage. Another loss she suffered was access to quality health care.

“If you’re in rural America, getting care is hard,” Gleason says. Along with a lack of providers who are competent in gender-affirming care, there are bills being introduced or enacted in states like Alabama, Kansas and Oklahoma that would criminalize minors from receiving treatments like hormone replacement therapy. In late March, Arkansas passed legislation banning gender-affirming health care for trans youth, and Mississippi and Tennessee recently banned school athetlics for trans girls and women.

Transgender people nationwide also face what is known as “trans broken arm syndrome,” where health care providers assume that every ailment is a result of being trans. Due to this level of discrimination, along with prohibitive costs and inadequate insurance, 40% of trans or gender-nonconforming people in Colorado report delaying medical care, according to the Colorado Transgender Health Survey results published in May 2018.

As a member of the Wichita LGBT+ Health Coalition and Equality Kansas, Gleason is dedicated to educating people throughout Kansas about queer health. So when she discovered ECHO, she knew it was something that providers in the state needed. She signed up for the bootcamp and spread the word, successfully recruiting nine other providers.

“It’s exciting to see that there are a lot of providers that care, that want to know more,” says Gleason. “ECHO is such a life-saving organization and the project that they’re doing is just truly a paradigm shift from where we’ve been.”

The COVID-19 pandemic has only served to reinforce ECHO’s necessity. Prior to the pandemic, driving to see a transgender specialist in a larger city like Denver was expensive and difficult for many patients. Now, there is the added concern of traveling safely during a pandemic, therefore restricting people to local clinics, or potentially skipping or delaying needed health care.

“The purpose of the ECHO model is to increase access,” says Leah Willis, the program director for ECHO Colorado. “COVID has really illuminated the need to ensure that primary care providers, wherever they are, have all the support that they want from specialists and academic medical centers in order to deliver high-value medical care to their patients.”

Currently, 153 providers have signed up for ECHO Colorado’s monthly classes on gender-affirming care that will continue throughout the rest of the year. Because of the program’s popularity, they plan to host another bootcamp soon.

Bullis is excited about the program’s growth. “I absolutely think that more providers moving forward will want to learn more of this stuff,” she said. “It is so necessary in primary care—I want this to be an open and safe experience for all patients.”